Riley, Jesse Dale. "Ultra Trio IV: Birds of Prey and Wind-Up Dolls. Ultrarunning. December 1990.

|

|

|

The Start of the 1,300 Mile Race: (l to r) Sri Chinmoy, Tony Raferty, Patrick Cooper, Christel Volmerhausen, Jesse Dale Riley, Bruce Holtman, Ronnie Wong and Charlie Eidel. |

The Sri Chinmoy Ultra Trio, including the world's longest footrace, celebrated its fourth edition recently with numbers and performances a little off last year's standard, but with its usual vast store of wisdom to impart to the athletes who took up the gauntlet and spared no effort to meet the challenge.

The 1,300 started with a duel between rivals from last year's seven-day race: Charlie Eidel, a truck driver from upstate New York with '1,300' shaved neatly into his crew cut, and Ronnie Wong, a 2:40-marathoner and underachiever at previous multi-days, who owns a restaurant in Baltimore. Wong's speed prevailed the first day as he rolled up 104 miles to Charlie's 10, but lurking just behind Charlie after staying on the road most of the night was Christel Volmerhausen, a 57-year-old German woman who had raced well here last year. Tony Rafferty, the ultra pioneer whose solo run from Sydney to Melbourne in Australia 15 years ago helped found the modern multi-day era, settled for 94 miles and fourth place. Digestive problems and a succession of injuries would drag him down to his worst multi-day effort ever. On day two Charlie pulled through Ronnie with 76 miles, Christel pulled another virtual all-nighter and the race was on.

|

|

The start of the women's 1,000-Mile Race. (L to r) Helene Westreicher, Antana Locs, Barbara McLeod and Essie Garrett. |

Day three heralded the start of the 1,000-mile women, with 16 days to complete their distance. Antana Locs of Montreal, hoping to set a new women's record, was clearly the class of this field. She and two more of Sri Chinmoy's disciples, Neli Lozej and Mary-Anne Trusz in the 700-mile that started three days later (all races had a simultaneous finish), formed a group we called, with a mixture of affection and envy, The Wind-Up Dolls, for their ability to cruise smoothly around the course without apparent regard for fatigue, weather, injuries, or the time of night. The 1,000-mile men, Al Howie and Dictino Mendez, were off and running the next day, but with only Al and Antana on pace to finish the entire distance, this race became for them, in Howie's words 'a 1,000-mile time trial,' with no more championship than the runners in the other races and their own dogged pursuit of excellence. To their credit, however, all but one of the thousanders stayed in the race to the end, and Mendez even set an American age-group record for six days, only to have it broken two days later by rival Richard Cozart in the 700. Mendez had beaten Cozart to the 48-hour record in a tight battle at Pensacola in January.

|

|

|

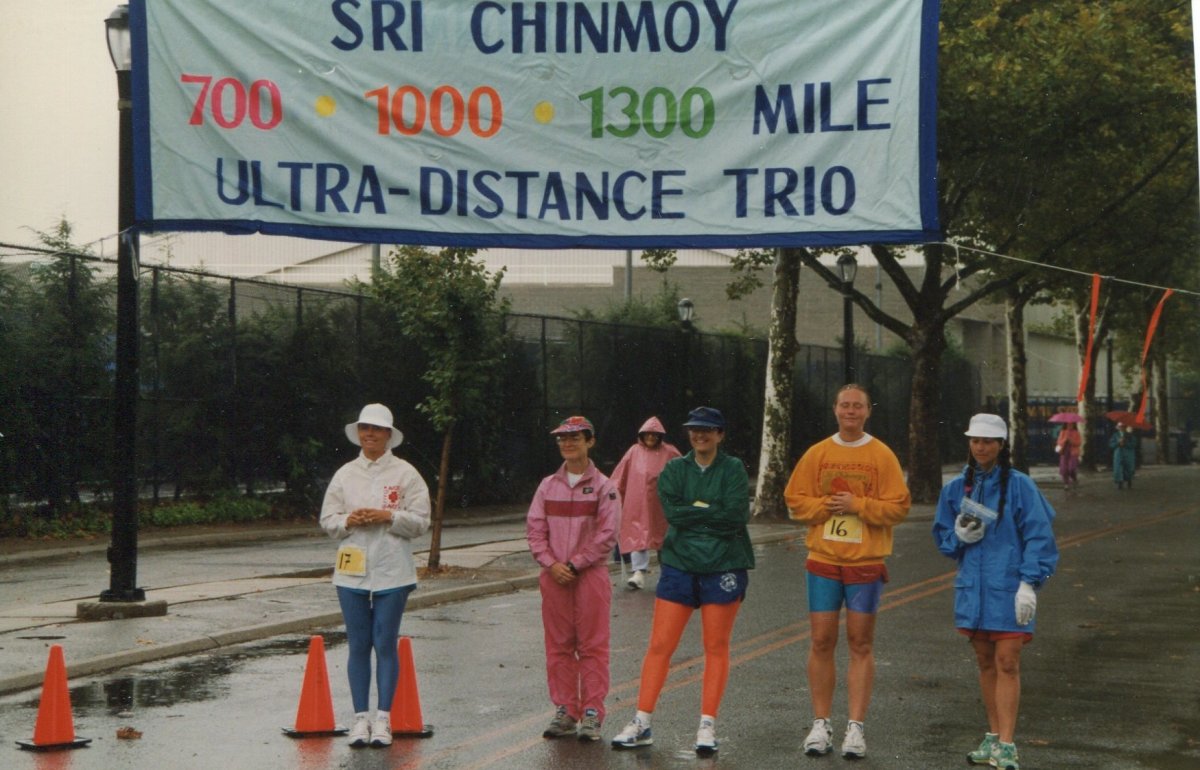

The start of the women's 700 Mile Race. |

The 700, conversely, proved to be a close, hard-fought race to the very end, with a colorful and unpredictable cast of characters. Laurie Dexter, the Anglican minister from Canada's Northwest Territories, was the favorite coming off a victory at the Nanisivik double marathon and hopefully a year wiser and stronger after getting a 24-hour PR on the first day of last year's 1,000 in wretched heat, and then falling prey to a classic injury-laden crash within a couple of days. He was joined by multi-day veteran Cozart, who was just coming off an eight-month period of injuries; hiking-style walker Method Istvanik of the incessant chatter; cockney lad Peter Hodson, whose faded, low-tech clothing and gear looked right out of 'Mad Max' and earned him the nickname 'Alien Warrior'; and of course the other two Wind-Up Dolls, both experienced and fitter than ever.

|

|

|

The scoreboard and counting areas for the 1990 Ultra Trio at Flushing Meadows Corona Park |

The 1,300-mile runners, meanwhile were nearing the first cut-off of 350 miles in six days, a milestone which tends to bring home to the runners how very long this race is. All seven made it, but three would drop out within two days, injured and unable to face the remaining work. This left Ronnie Wong and Christel Volmerhausen to battle it out up front, a struggle we found endlessly amusing for its cultural implications. Ronnie, a Singapore native, seemed deathly afraid of losing to a woman, and gave Christel the bitter nickname of 'The Vulture.' Christel, a short, unimposing woman who was a great favorite with us, assumed that methodical, victory-or-death attitude that seems to come naturally to the Germans. A typical incident occurred on the sixth night at about 2:00 a.m. when Ronnie, no doubt irritated at having to stay up all night to keep ahead of 'the old woman' (he never called Christel by name), challenged Christel to a mile race. He won, but immediately retired to his tent, while Christel, winded but dauntless, trudged on. She closed to within eight miles in the middle of the race, but at length Ronnie pulled away to lead by 58 miles when time ran out on both of them. This is the third time in four editions that this race had no finishers. Christel, who set all manner of records on her way to a strong finish, including 431 miles the first six days (woman's over 50 world best), blazed a trail by becoming the first woman to go past 1,000 miles, finishing with 1,119, right at 100 km per day.

|

|

|

Essie Garrett (l) and eventual 1,300 mile winner Ronnie Wong circuling the Unisphere at the Sri Chinmoy Ultra Trio at Flushing Meadows Corona Park. |

Antana Locs blasted out to a 48-hour split of 175 miles in the 1,000 and made a 40-mile cushion for herself above world-record pace, but still needed 64 miles a day, a pace she was hard put to maintain. Grudgingly giving back the miles that had cost her such an effort early on, she didn't finally fall behind until day 12, when she had her shortest day of 52 miles. Now she was forced to relent in her attempt at the record, but she still recorded a good performance - her splits increased over each of the following days until she came gracefully across the line 13 hours over the record. Al Howie was also finding himself a little behind his goals, apparently because in the six months before the race he had taken the unusual step (for him) of getting a regular job (planting seedling tress in the Canadian wilderness). This has been the undoing of many fine multi-day addicts. Fortunately he had no pressure from behind, his phenomenal talent asserted itself, and he ran himself into shape by the end, pulling through 91 miles in the final 22 hours to finish nine hours over his 1,000-mile split from last year's record-breaking win in the 1,300.

Back in the 700, history was repeating itself as Laurie Dexter again put in over 100 miles in the first day and began to fade soon after. Neli Lozej and Mary-Anne Trusz took it conservatively and throughout the race found themselves within a few miles of each other, until Neli pulled away on the last day to win by ten hours. Richard Cozart, slow and steady, held the lead for five days in the middle of the race before injuries slowed him to a crawl and left him 45 miles short when time ran out. Method 'The Pendulum' Istvanik, 63, cranked out an endless succession of 16-minute walking miles and was off the track only half an hour the first day. He slept a little the second day, but his relentless ways earned him a 48-hour split of 156 miles, a rare achievement for a walker and less than 20 miles off the American record for runners in his age group. Needless to say, this touched off an animated debate over whether the diminutive pedestrian was for real. An hour into Day three he passed the fading Dexter and assumed the lead. 'That guy's beginning to get on my nerves,' said the normally easygoing Peter Hobson, and he picked up the pace to lure Method, who was pacing of him. As soon as that, it was over. Method finally took a decent rest, awoke no doubt broken in mind and body, packed up his gear, and left the race without a word. Come see us again, Method. You're awesome, buddy.

|

|

|

700 mile winner Peter Hobson of Great Britain. |

After five or six of the nine contestants had held the lead, a shockingly fresh Peter Hodson, 36 of Godmanchester, England, came home in front. His shabby gear, green, springless Ron Hill sneakers ('ballet slippers,' Tony Rafferty said, shaking his head,) and thick cockney accent kept us in the dark for much of the race about his ability, but when it dawned on us that Peter was taking a full, eight-hour sleep each night and making up 50 km on Richard Cozart during the day, we realized that this was an uncommonly talented runner. Far from being pressured or anxious, he never arose in the mornning without a hot shower and shave, a toothwash, a detailed examination of the standings, breakfast, and a social call at Al Howie's tent. In fact, it was with some difficulty that we persuaded him to remain on the track for a few extra hours that last night, rather than 'have a kit' (got to bed) and finish in the morning. A veteran of over 100 marathons and several ultras, he seems to value participation over results, although he finally achieved a serious attitude, and perhaps a small tear as well, when a chorus sang God Save the Queen in his honor after he received his trophy at the awards ceremony.

I remember Stefan Schlett asking me in jest, one week into the 1,300 last year, 'Which is worse, the end of the world, or this race?' Stumped for a reply (or maybe I couldn't decide), I let him answer his own question: 'The race is worse,' he said, 'because it lasts longer.' When this track meet began in 1987 a lot of people, both in running and out of it, shrugged it off as too much of a good thing, or even too much of a bad thing. Certainly a race like this, involving so many 'non-running' elements like sleep deprivation, camaraderie, patience, digesting huge amounts of food (in my case, at least), and performing in the face of crippling injuries and hopeless odds, often bears little resemblance to a 50-mile or 24-hour race. For me, though, this is an event that is ahead of its time. When I saw an account of the first Trio in a small regional running paper I recognized a chance to find out what it was like to run all the time, without the interference of a job, household chores, or an uncaring or antagonistic public, and after I bowed out the following year with less than half the job done after 13 days on the road, I, in common with most of the other challengers, came away with a different perspective on the sport and on things generally. Sri Chinmoy is convinced that this event will one day be he crown jewel of ultra marathoning and promised next year's event will have even more side events, more publicity, and more runners. I can't wait.