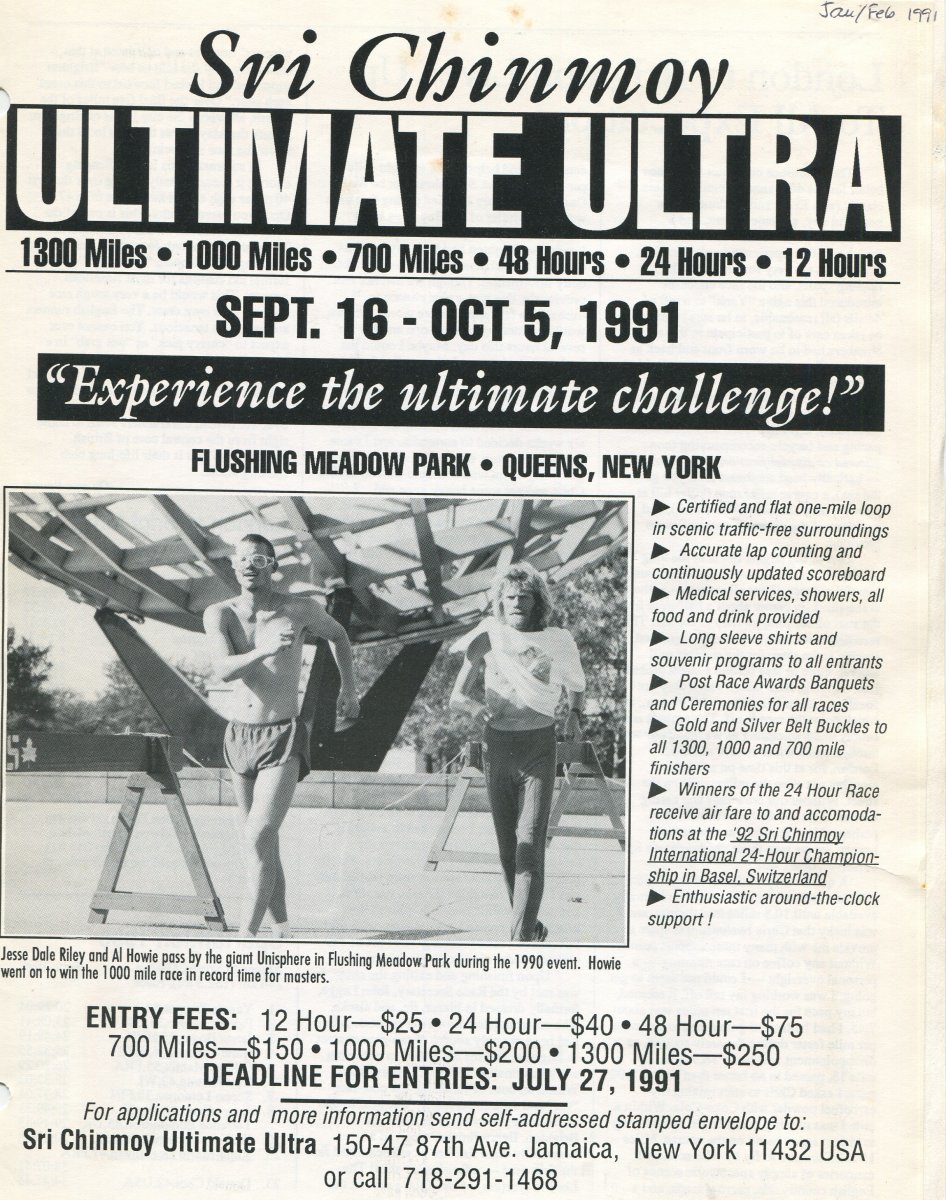

Jesse Dale Riley describes his 1300 Mile Race experience in “The Ultimate Ultra: Lord of the Rings, Down by the Freeways.” Riley, Jesse Dale. Ultrarunning. December 1991. The Sri Chinmoy Ultimate Ultra took place September 16 - October 5

Jesse Dale Riley describes his 1300 Mile Race experience in “The Ultimate Ultra: Lord of the Rings, Down by the Freeways.” Riley, Jesse Dale. Ultrarunning. December 1991. The Sri Chinmoy Ultimate Ultra took place September 16 - October 5

On a slow day in New York City (if there is such a thing), round about late September, down by where the freeways meet south of the East River near the small, murky green slough that is the last survivor of he swamps that once ruled Long Island, where the overpasses shelter the homeless men who gather in the evenings to roast whatever meat the day’s scavenging has brought, amid sounds of explosions from the vehicles above, which tear headlong over the crumbling pavement, seemingly bent on suicide, you can pick out a square of turf, lay out your blanket, and watch a series of haggard runners make slow rings around an inconspicuous section of Flushing Meadow Park. The athletes have gathered here, after long journeys from Europe or Asia or the hinterlands of this country, ignoring threats of divorce from their spouses or termination by their employers, mindful of promises made to sponsors back home, ready to contest a sort of mental marathon, where the numbing repetition of the course lays to rest memories of the world beyond the barricades, until the only reality is the rhythm of slowly increasing pain and fatigue balanced by confidence in the descending mileage left to run.

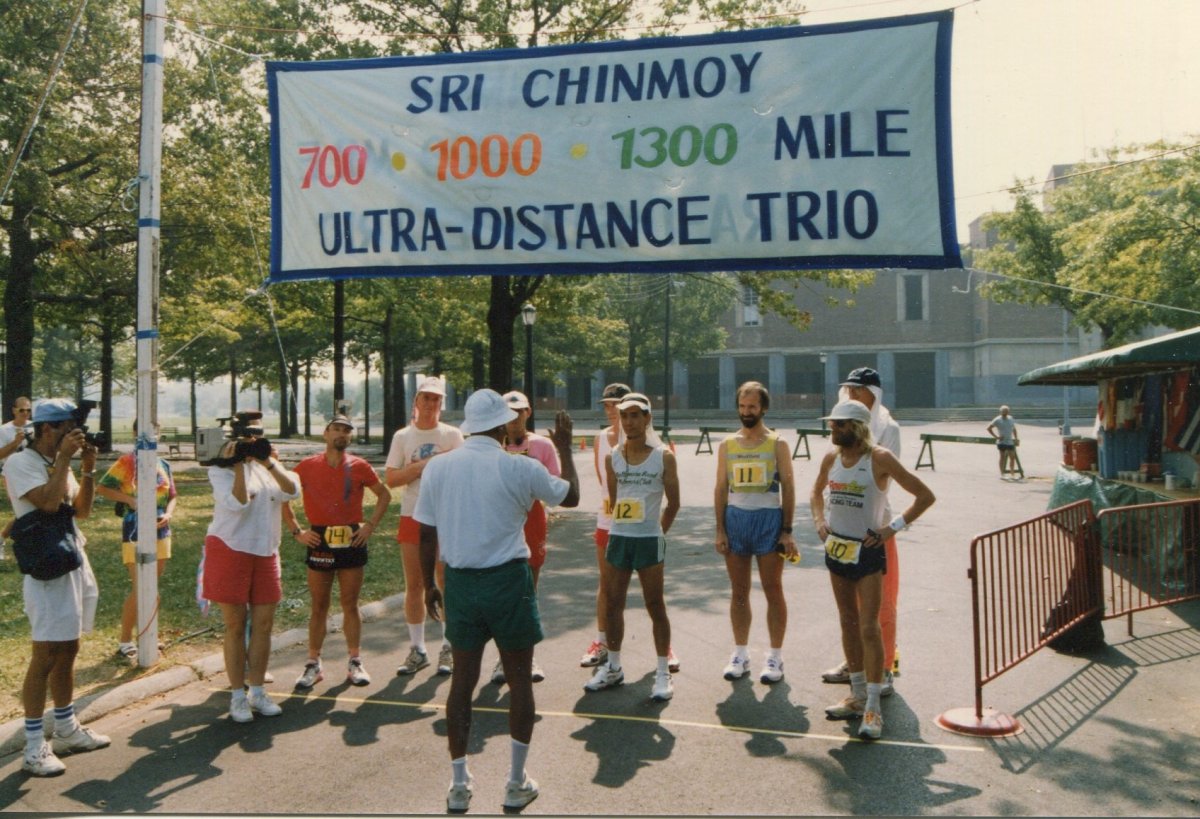

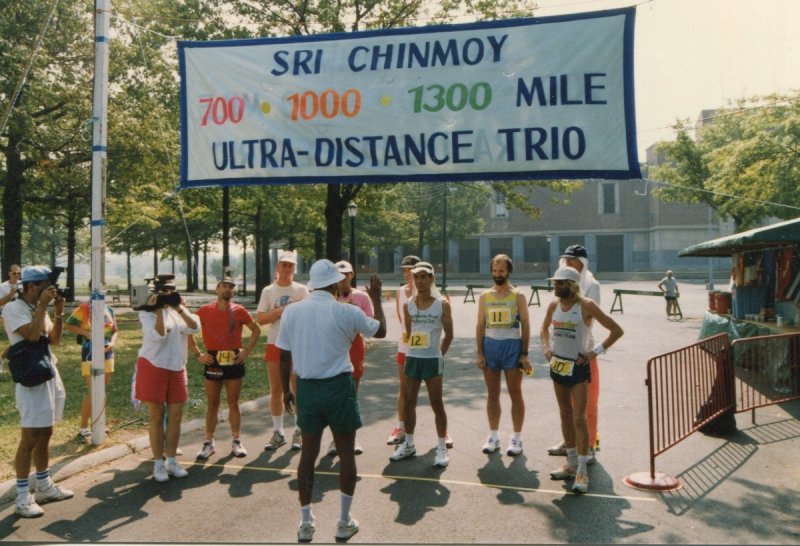

Sri Chinmoy offers his best wishes to men's 1,300 mile runners: (l to r) Emil Laharague, Simahin Pierce, Trishul Cherns, Bruce Hotlman, Ronnie Wong, Marty Sprengelmeyer, Jesse Dale Riley and Al Howie.

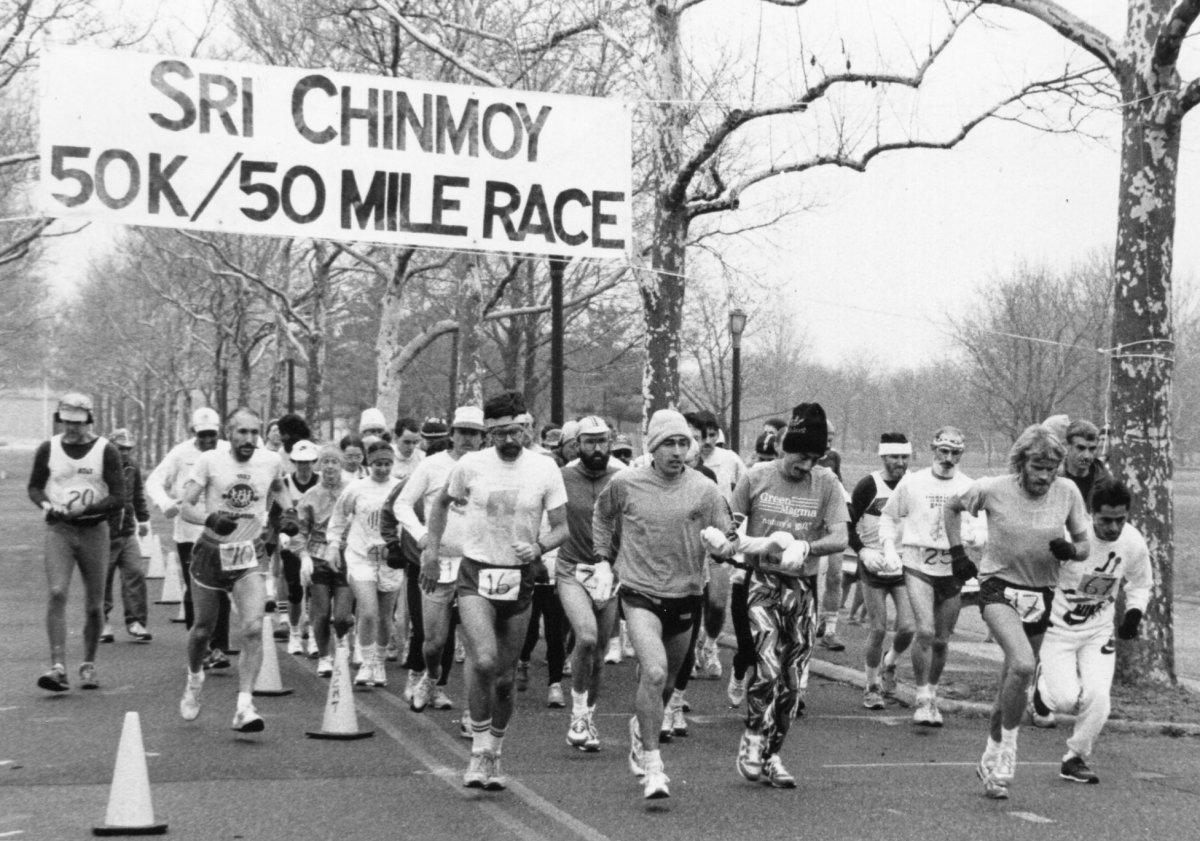

The renamed Ultimate Ultra, now in its fifth year as a trio of races 700, 1,000, and 1,300 miles long, kicked off on September 15 and for once you couldn’t tell the competitors apart without a scorecard. Fully 61 people from 13 countries sowed up, including 37 in the 700-mile, which made it the largest multi-day race in the U.S. in years.

Back to defend his 1,300-mile record from 1989 was Al Howie, only 15 days after averaging 63 miles a day for ten weeks in a record run across Canada. New Zealander Sandy Barwick on the women’s side returned after a three-year absence, a much better runner than when she set the 1,000-mile record in 1988 (broken a year later by Suprabha Schecter); last November Sandy ran 549 miles in six days at Campbelltown, Australia. Of the other 12 men and women in the 1,300 all but one had run at least a six-day before, seven had run 1,000 miles.

Dan Coffey of London, England.

Dan Coffey of London, England.

In the 1,000, however, only 60-year-old Brit, Dan Coffey, the beloved ‘Clockwork Mouse,’ had covered the distance before. Instead, three specialists at shorter distances, Tom Possert, Arpan De Angelo, and Hungarian Istvan Sipos, lined up with neither experience nor fear of running 70 miles a day for two weeks.

Likewise the 700 exhibited only one clear favorite, defending champion Peter (‘The Alien Warrior’) Hodson, who would never have to buy another candy bar if he could only remain in the States through Halloween. However, Peter faced the most talented newcomer of them all, world-class 100-km man Tomas Rusek of Czechoslovakia. The other men and women in the 700 were an unpredictable potpourri of varying specialties and talents.

The format, staggered starts and a simultaneous finish, had the 1,300-mile women off he line first and Sandy Barwick pushed ahead with 112 miles on Day One. The men began at noon the next day with an 18-day time limit and soon there was trouble. The problem was the heat. The sun was unusually strong, the only shade was the overpasses, humidity was about 70 percent, and the temperature climbed into the mid-90s. By the four-hour mark only four men had made even 20 miles, and the women, already faced with the usual second-day letdown, were sinking into shock. Sandy and Antana Locs persevered and rolled up good mileages, ut by the end of the second day the other four women were already all but out of contention to finish. The men, too fresh to bail out, struggled to first-day totals that averaged 13 miles less than the women’s.

The start of the women's 1,300 mile race. (r to l) Antana Locs, Cristel Vollmerhausen, Renate Nierkens, Sandy Barwick, Suprabha and Helen Westreicher.

Days three and four were more of the same, as even the nighttime temperatures had stayed in the high 70s. ‘One more hot day and I’m out,’ said a disgusted Renate Nierkens in German; her best multi-days had been cold weather affairs. The enigmatic Emile Laharrague, who seems to de-materialize when he’s not scheduled for a race or other adventure, went out slow. His age old malaria, contracted in an African jungle some years ago, re-occurs in hot weather. Suprabha Schecter, winner of the last seven multi-days she’s entered – an incredible feat – was in dire straits. Crawling along at a rate we’d never before seen from her, she seemed unable to comprehend her deteriorating condition, and it took a good deal of persuasion to get her off the track. Once off, though, the disciples really went to work. They laid out her cot in a breezy, shady sot, brought her favorite foods and fruit juices, and coaxed her into a long rest. Twelve hours later she was back on the road, once again the relentless foot soldier that we’ve grown to love.

Day five brought the 1,000-mile men to the starting line and an almost simultaneous change in the weather – rain! Lots of it. By now, we were so crushed by the heat that the chance to shiver in wet clothes seemed like a good thing, but soon we’d grown tired of that as well. The 1,000-mile runners presented a confusing spectacle as they splashed through deep puddles on the course. Istvan Sipos would charge around for 10 or 20 miles at a time, only to stop for long breaks and chat with his family, who had accompanied him en masse from the continent. One gear down was Arpan De Angelo, in a nervous haste to get it over with. Charlie Eidel and Dan Coffey (who caught a late flight from London and started 12 hours after the others) trotted along waiting for something interesting to happen, while Tom Possert took to walking so he could talk to the 1,300 mile runners. Within a couple of days the gossip mill had cranked up, and we had their stories sorted out.

Day five brought the 1,000-mile men to the starting line and an almost simultaneous change in the weather – rain! Lots of it. By now, we were so crushed by the heat that the chance to shiver in wet clothes seemed like a good thing, but soon we’d grown tired of that as well. The 1,000-mile runners presented a confusing spectacle as they splashed through deep puddles on the course. Istvan Sipos would charge around for 10 or 20 miles at a time, only to stop for long breaks and chat with his family, who had accompanied him en masse from the continent. One gear down was Arpan De Angelo, in a nervous haste to get it over with. Charlie Eidel and Dan Coffey (who caught a late flight from London and started 12 hours after the others) trotted along waiting for something interesting to happen, while Tom Possert took to walking so he could talk to the 1,300 mile runners. Within a couple of days the gossip mill had cranked up, and we had their stories sorted out.

Tom, for whom 100 mile is only 14 hours work on a good day, felt that 90 miles a day was a reasonable goal and, since he could walk 12-minute miles easily at the start and run nine-minute ones, he was in no hurry to proceed. Forty hours into the run, however, reality set in. It’s not as easy as it looks! His feet were hurting from all the walking that he wasn’t used to, and he was reduced to three miles an hour. He scoured his brain for an excuse that would allow him to withdraw honorably, but fortunately found none. Like Bruce Holtman and Ronnie Wong in the 1,300 Tom was running for a charity back home. Nothing to do but make the best of it and start jogging 14-minute miles, like everyone else. Istvan continued to pass everyone while he was on the track, but stuck to a conservative plan of 72 miles a day and got plenty of rest. Sponsored by a travel agency (which explained how his whole family had managed to make the trip), he needed only to finish to get an invitation to the Sydney-to-Melbourne Race, and consequently was reluctant to push the pace. Charlie Eidel, who felt he was the rightful favorite after a strong win in the seven-day race in May, waited in vain for Tom and Istvan to fold. Arpan had a great first day and then settled in for a long death-march to the finish. Dan Coffey made decent progress toward a 1,000-mile world over-60 record, but would eventually bail out after 1,000 km.

Tom, for whom 100 mile is only 14 hours work on a good day, felt that 90 miles a day was a reasonable goal and, since he could walk 12-minute miles easily at the start and run nine-minute ones, he was in no hurry to proceed. Forty hours into the run, however, reality set in. It’s not as easy as it looks! His feet were hurting from all the walking that he wasn’t used to, and he was reduced to three miles an hour. He scoured his brain for an excuse that would allow him to withdraw honorably, but fortunately found none. Like Bruce Holtman and Ronnie Wong in the 1,300 Tom was running for a charity back home. Nothing to do but make the best of it and start jogging 14-minute miles, like everyone else. Istvan continued to pass everyone while he was on the track, but stuck to a conservative plan of 72 miles a day and got plenty of rest. Sponsored by a travel agency (which explained how his whole family had managed to make the trip), he needed only to finish to get an invitation to the Sydney-to-Melbourne Race, and consequently was reluctant to push the pace. Charlie Eidel, who felt he was the rightful favorite after a strong win in the seven-day race in May, waited in vain for Tom and Istvan to fold. Arpan had a great first day and then settled in for a long death-march to the finish. Dan Coffey made decent progress toward a 1,000-mile world over-60 record, but would eventually bail out after 1,000 km.

Meanwhile Sandy Barwick and Al Howie and rolled up 50-mileleads in the 1,300 and were well on their way to epic marks. Both passed the six-day split with over 500 miles and plenty of reserve still left, and pulled their challengers along to times hardly thought possible five years ago. Easygoing Marty Sprengelmeyer and road-fried Trishul Cherns were a study in contrasts as they battled it out for second place among the men, while the Baltimore Boys, Bruce Holtman and Ronnie Won, tried hard to remain friends while wrestling for fourth. Antana and Suprabha were well clear of each other and the women behind them, their intensity and apparent fatigue masking great performances.

Meanwhile Sandy Barwick and Al Howie and rolled up 50-mileleads in the 1,300 and were well on their way to epic marks. Both passed the six-day split with over 500 miles and plenty of reserve still left, and pulled their challengers along to times hardly thought possible five years ago. Easygoing Marty Sprengelmeyer and road-fried Trishul Cherns were a study in contrasts as they battled it out for second place among the men, while the Baltimore Boys, Bruce Holtman and Ronnie Won, tried hard to remain friends while wrestling for fourth. Antana and Suprabha were well clear of each other and the women behind them, their intensity and apparent fatigue masking great performances.

Day seven brought the 700-mile women and Bihagi Muischneek, a young Swiss disciple of Sri Chinmoy, took control early with 104 miles the first day. Few runners of any ability would care to knock out a distance like that and still continue on for two more weeks, a point that seems lost on those who think multi-days only attract slow runners. Two days later the pack had reeled in Bihagi, and a tight battle ensued over the next four days before she relinquished the lead for good. The men’s 700 was over as soon as it started, or so it seemed. Tomas Rusek dashed off at eight minutes a mile and rolled out an incredible 130 miles the first day, despite four hours sleep. Patrick Cooper, Richard Cozart, and Hodson followed, light year behind.

Once all the races had started and life on the loop settled into a routine, everyone had a different or beating the boredom. Anticipating our parole was the favorite by far. First off, we were going to eat and eat until this great country was one big culinary desert, utterly devoid of pepperoni pizza and Haagen-Dazs ice cream. One of the disciples entertained us by setting a Guinness record for non-stop guitar playing in conjunction with the race. It was worth money to go into porta-johns sometimes and suddenly hear gentle strumming in between certain other sounds coming from the next booth. Sandy’s handler helped keep her awake with a real luxury, steaming towels that she had wet and put in the microwave. Peter Hodson kept on one the park’s homeless men awake. The poor guy probably had nightmares for a week after Peter confronted him over a water bottle the guy had collected off the course and put in his plastic garbage bag, along with several dozen aluminum cans. Peter has very pale skin, keeps his hair prisoner-short, wears faded clothing, and speaks a language that sounds disturbingly like English. The shaken fellow, who looked like he was about to take up running himself, albeit in the opposite direction, handed over Peter’s bottle with some trepidation, hesitated for a second, and then asked, ‘Do you want the cans, too?’

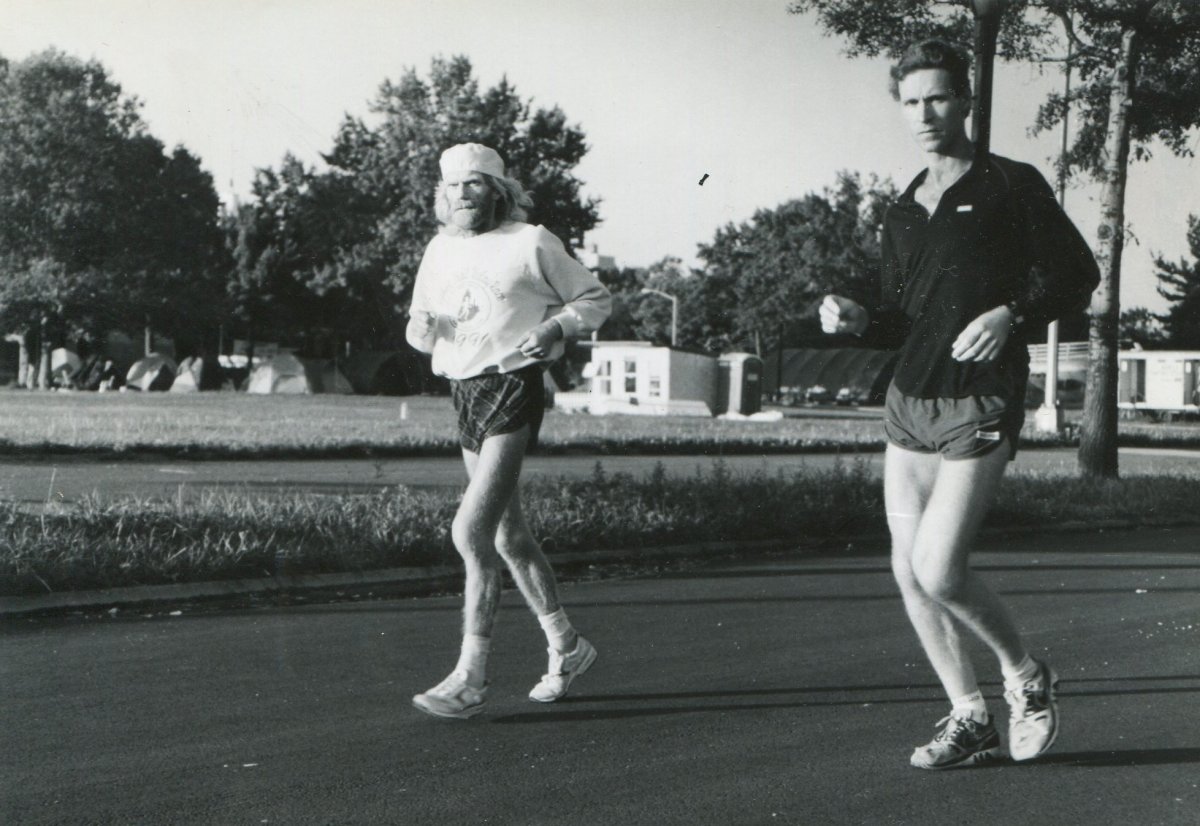

Al Howie (l) and Tom Possert pass the camp area. Possert went on the win the 1,000 mile race in 13 days, 14 hours, 2 minutes and 52 seconds.

Day ten brought a few changes in the standings. Tom Possert’s handler had to head back to Cincinnati, and his girlfriend wouldn’t be arriving until the following day, so with no one to crack the whip Tom was soon in the sack and in fourth place, after having had a 30 mile lead. Marty passed Trishul in the 1,300 and held onto second the rest of the way, while Suprabha made only 40 miles and fell behind pace to finish the entire distance. True to form, though, Suprabha never gave up and pulled through 60 miles a day the rest of the way to make 1,200 miles. Tomas Rusek in the 700 was beginning to realize that he had badly miscalculated with all those hard early miles, and everyone noticed that he was no longer extending his lead over the chase pack. It seems that Rusek had run with James Zarei at a marathon-a-day stage race in France last June and found out that Zarei, who was no match for him there, had run 1,000 km in six days before, a great mark. Rusek naturally felt he could o it as well. Apparently, however, Zarei failed to tell the now-chagrined Tomas that he needed to stay on the track almost continuously, sacrificing sleep so as to make the slowest possible pace. Instead Tomas had blitzed the course, and was rapidly being corned by blisters, cramps and swelling.

A rare moment of rest while she soaks her tired feet, Dipali went on the win the 700 mile race with 670 miles.

By day thirteen Al Howie and Sandy Barwick were pulling into the 1,000-mile split pretty hurting, but with huge leads. Sandy had really gone for broke and nearly took the overall masters record from countryman Siggy Bauer, a formed world-record holder who can now claim to be the second best ultrarunnner in New Zealand. Sandy came in 53 hours under the old record, something even Kouros couldn’t hope to do, after lowering it by over 50 hours in 1988. She paid the price, however, as she had to walk it in from there with a puller hamstring and a panicky crew who felt Antana, over 100 miles behind, was still a threat. Howie pulled into the 1,000 with the new masters record and talking abut having a go at Kouros’ mark of ten days, ten hours next year. Far from being shook up by his recent trans-Canada run, Al was in superb condition, and I couldn’t help but think that is here were another multi-day a couple of weeks after the 1,300 he would do better still.

By now were were counting out Tomas Rusek. He hadn’t been seen on the track in almost a day and the only reminders of this great run gone sour were the paper Czech flags he had planted around the course. ‘Look, they’re all flying at half-mast today,’ joked Tom Possert. Tom himself had regained confidence and was running negative splits and leaving the other 1,000-mile runners behind, the only runner in any of the races that still seemed capable of 80-mile days. Bhikshuni Weisbrot jumped the field in the women’s 700 moving from fourth to first on the seventh day out and setting breathtaking PRs across the board. She was the last woman on pace to finish the 700, so it was sad when she faltered a couple of days later. John Surdyk of Chicago missed the cut in the 700 and headed home with the classic remark, ‘I better not miss the Bears game ‘cause of this.’

Sandy Barwick's historic finish: the first female to finish the 1,300 Mile Race and a new women's world recordfor 1,000 miles.

Renate Nierkens, like a lot of us, was getting philosophical toward the end. She had performed well in difficult conditions, but the leaders had buried her. Was it worth it? She thought it over for a moment and then brightened when she remembered all the freeway overpasses – we had passed seven on each lap heading out to the turnaround, plus the same seven on the backside, so that gave her just over 15,000 total in 1,100 miles. ‘It’s a German record for running under bridges,’ she said. Even the jaded New York media got in the spirit of things. The Times and several TV stations turned up and filed reports that emphasized, amazingly enough, that an ultra can be a comedy or a tragedy, depending on which scene you walk into, and that people participate for a lot of different reasons that they don’t always understand themselves. By then I was scuffing along in last place in the 1,300 and feeling the effects o the 3,000 miles I’d run in Canada over the summer. I’d eaten 300 PowerBars during the race and my one remaining motivation was to get some publicity for the folks in Berkeley. One of the local news teams was only too happy to oblige, and kicking back after the race to watch myself on TV was the ironic highlight of the whole contest for me. Yes, it was worth it.

Sri Chinmoy (2nd from r) with new world record holders Al Howie (r), 1,300 mile and world masters 1,000 miles, and Sandy Barwick (3rd from right), women's world record 1,300 miles and 1,000 miles. Author Jesse Dale Riley (l) applauds the two champions.

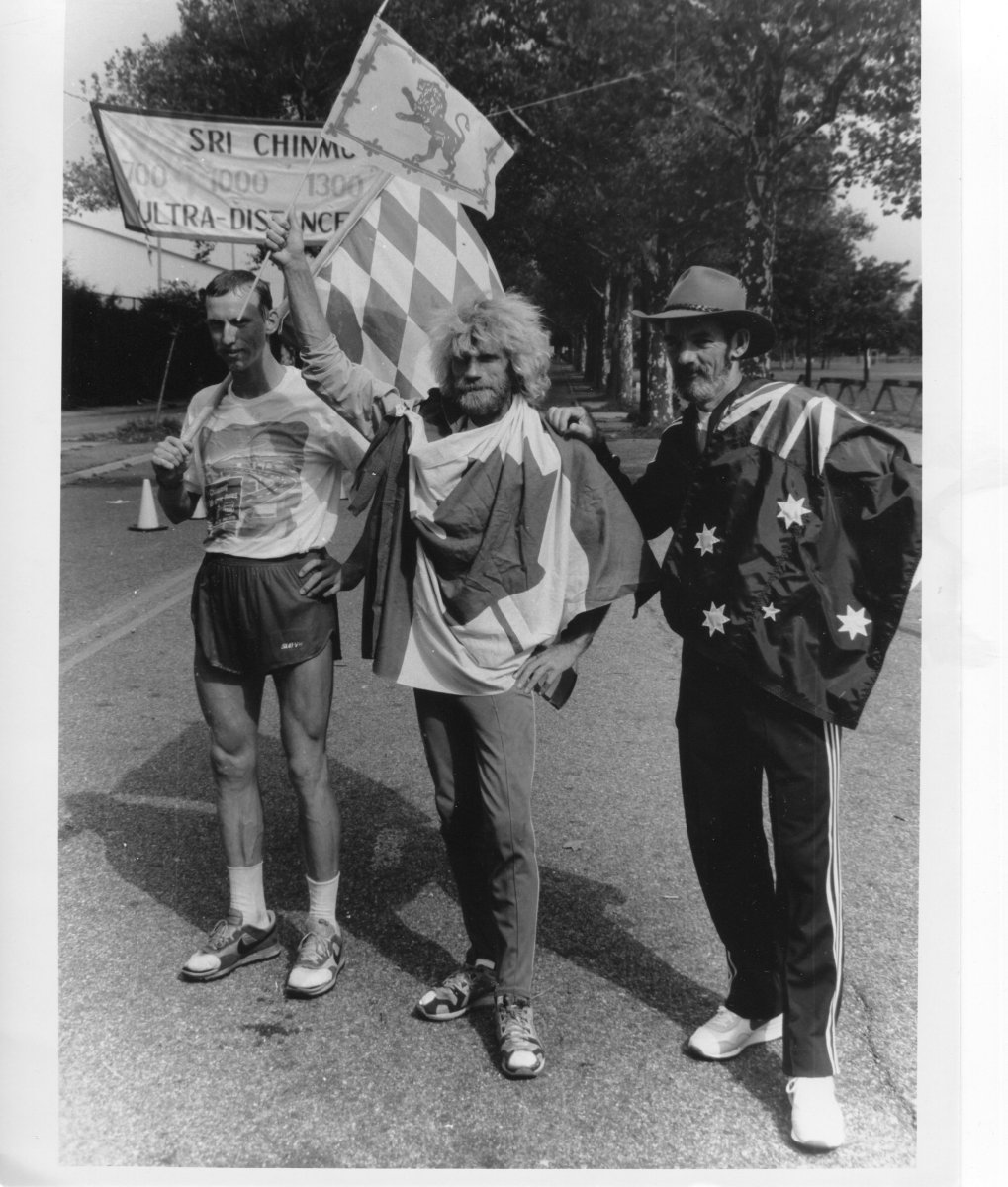

‘The problem with these eastern Europeans,’ said Peter Hodson, looking on as a rejuvenated Tomas Rusek spun by the lap counting station, ‘it they take everything so seriously.’ Peter had watched and waited, he had pushed himself more than last year, raising his super-efficient gait to a new art form (with arms straight down and no bounce, Peter shifts speeds instantly without breaking stride), all to no avail. Tomas was just too tough. After a 40-hour break, Rusek had rejoined the fray on Day fourteen; walking at first until Peter came within fur miles of him. Then he blasted off, getting stronger and stronger until he cleared mammoth 92 miles on day seventeen, almost doubling Peter’s output for the day.

Tomas finished before everyone else, almost two days ahead of his cut-off, clearly relieved the ordeal was over. The 40-year old librarian from Vinohrady, Czechoslovakia, a 2:22 marathoner, had found that the streets in the U.S. aren’t paved with gold. There’s big potholes that fill with rain and mud, two-foot rats that will steal your dinner if you set it down for a moment, running shoe stores arrayed with gorgeous, high-tech merchandise that costs a small fortune in your native currency. You couldn’t have prepared for what you’d find in New York City, Tomas. We all wanted to believe, though, that you could somehow adjust to your strange new environment and get 700 miles from your lone pair of size 13 Nikes, and when you beat your injuries and the odds to cross the line first, we were all mightily proud to have run with you. Welcome to America, buddy.

|

|

As the other nine finishers shuffled in over the last couple of days, there was a small ceremony for each of them at the start area and recognition of the marks they had made. Beyond the numbers and records, though, they could draw on a sense of mastery over an epic challenge. For the majority who ended the race many miles short o the goals they had felt destined to reach when they set out weeks before, the course would remain in their minds the lord of the rings, along with the little patch of new York City that it encircles, down by the freeways.

Thoughts on the 1991 Sri Chinmoy Ultra Trio: 700/1,000/1,300 Mile Races

Thoughts on the 1991 Sri Chinmoy Ultra Trio: 700/1,000/1,300 Mile Races

Robin Finn, October 3, 1991, The New York Times

"Just like her fellow ultra-marathoners, Sandy Barwick, a New Zealand housewife whose one peculiar avocation has turned her into a world- record holder, is living out of a tent in the midst of a multinational nomad camp along the boat basin at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

It is a place where almost everyone moves at a limp, where the tent that contains the MASH unit administers continual treatment to runners suffering ailments ranging from simple blisters to the dementia that comes from running the same one-mile circle, like a gerbil on an exercise wheel, over and over again for two weeks with only a few hours of sleep each day."

Photo: Race Founder Sri Chinmoy greets the runners at the start of the 1,300 Mile Race

Whiting, Nathan. "From the Big Apple: The Ultimate Challenge. Ulrarunning. September 1991.

Whiting, Nathan. "From the Big Apple: The Ultimate Challenge. Ulrarunning. September 1991. What interests me is that it was 200 years before there was a finisher. This challenge seems a little more ultimate, a goal we can’t reach or our children or their children…yet someday in another age it will be done. No T-shirt for 200 years, no trophy. A great thing about ultrarunning is the patience. We resist the American tendency for quick and obvious gratification. We look for the task somewhere close to the limits of our endurance. ‘What can be done?’ We combine the conservative idea of sticking to our goals. With a radical, almost rebellious urge to do the unthinkable, to defy the rules, at a time most Americans are splitting these ideas apart.

What interests me is that it was 200 years before there was a finisher. This challenge seems a little more ultimate, a goal we can’t reach or our children or their children…yet someday in another age it will be done. No T-shirt for 200 years, no trophy. A great thing about ultrarunning is the patience. We resist the American tendency for quick and obvious gratification. We look for the task somewhere close to the limits of our endurance. ‘What can be done?’ We combine the conservative idea of sticking to our goals. With a radical, almost rebellious urge to do the unthinkable, to defy the rules, at a time most Americans are splitting these ideas apart. If there is one point I have tried to make in these articles it is: we are up to something important. As a group we have made amazing discoveries. What we have not done well is record our discoveries, what we know, what we don’t know, what we feel, what we still want to feel. One reason is we’re too busy running. Another reason is we believe no one cares. Another reason is we run with people who have a pretty good idea already. The most important reason is it’s simply too hard to express it all, to hard to organize feelings, times, distances, and reasons into words. Ultrarunning have been popular before only to die out, be forgotten, to be started again from ignorance by a new generation. I don’t believe this is a good way to keep our knowledge alive, visible, present.

If there is one point I have tried to make in these articles it is: we are up to something important. As a group we have made amazing discoveries. What we have not done well is record our discoveries, what we know, what we don’t know, what we feel, what we still want to feel. One reason is we’re too busy running. Another reason is we believe no one cares. Another reason is we run with people who have a pretty good idea already. The most important reason is it’s simply too hard to express it all, to hard to organize feelings, times, distances, and reasons into words. Ultrarunning have been popular before only to die out, be forgotten, to be started again from ignorance by a new generation. I don’t believe this is a good way to keep our knowledge alive, visible, present.