The following is taken from the September 1989 issue of UltraRunning and reprinted by permission from the Publisher, John Medinger

Henry, Mallika."Sri Chinmoy Seven Day: Good Spirits Despite the Storm". UltraRunning. September 1989.

"In that inconspicuous corner of Flushing Meadows Park between the Unisphere and Shea Stadium which several times a year becomes a small hamlet of tents and plywood building, 21 runners gathered for the start of the Sri Chinmoy Seven Day Race. Despite the rain predicted for the week, each starter is ready to tackle his or her own race.

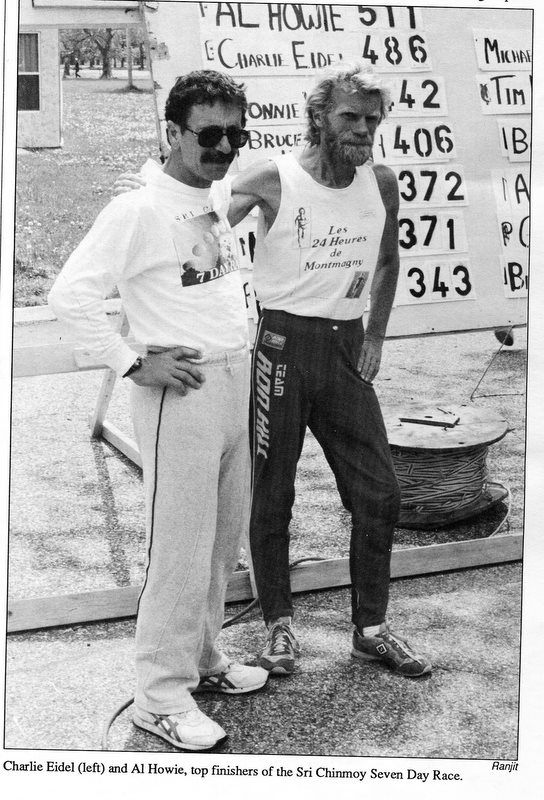

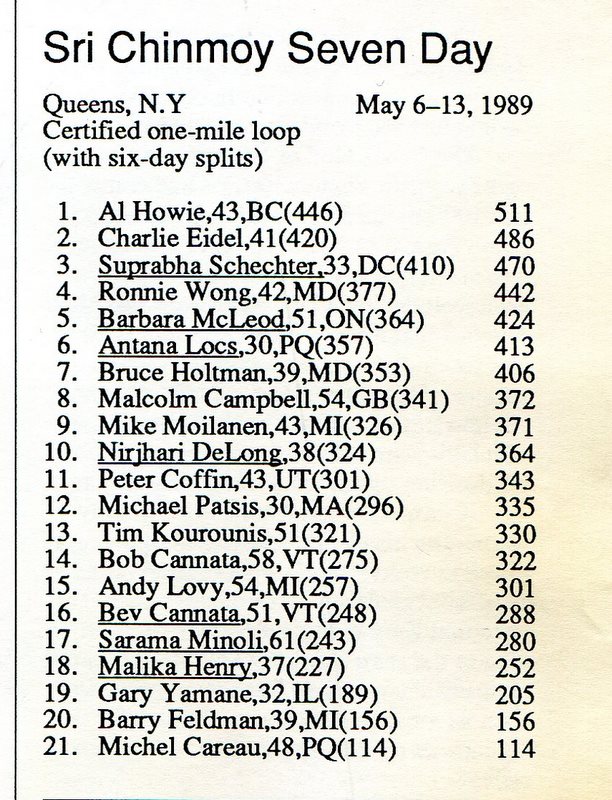

From the starting line of this year’s edition the results look pretty well stacked: there was veteran journey runner Al Howie, a very determined Barbara McLeod, Malcolm Campbell, whose longevity in the sport inspires awe, but who has just finished 500 miles in the Pan am flight 103 memorial stage race, and several others.

After an introduction and some group shots, we take off, to Sri Chinmoy’s vociferous “Good luck to you all!â€

Al Howie, in his tartan short, means to hold the lead, running as if it were a 100-mile race, with Michel Careau at his heels. Ronnie Wong from Baltimore begins his courageous performance and is steady day and night running in their wake. Tim Kourounis, who will also reach 100 miles in the first 24-hours, follows behind.

Leading the women after an exhilarating day one was Suprabha Schecter, whose delicate, almost dreamy appearance mystifyingly belies a startling tenacity which nearly won her the race overall last year. She is only ten miles behind Al Howie. Canadians Antana Locs, looking very strong with 100 miles at 24 hours, and Barbara McLeod were close behind.

Day two is often the hardest day of a multiday race, as the realities set in and the first day’s high mileage takes its toll. Flushing Meadows Park on a Sunday presents the additional challenge of partying humanity. Al Howie, eyes fixed on the sky, battles the day-two blues while Charlie Eidel, thoroughly prepared and displaying a dogged determination with his steady gaze fixed on the pavement a few feet ahead of him proceeds deliberately in hopes of a win. He moves into second, three miles behind Al, watching his competition closely. His training partner, Tim Kourounis, drops significantly off the pace with stomach trouble. Michael Patsis of Massachusetts strikes out in his first multiday with the second-highest mileage of the day, climbing into fourth place. Suprabha, undaunted by her 105 miles of day one, holds onto third, two miles behind Charlie, and McLeod passes her younger Canadian friend with the third highest mileage of the day.

The other Canadian, Michel Careau, becomes a casualty as a painful kidney stone sidelines him. And Malcolm Campbell, who has run about 40 more ultras (total 100) than any other runner in the race, keeps at a very respectable fourth place.

By late evening the park subsides, families leave for home with their barbecues and innumerable children. Even the soccer players finally finish their games. And the runners keep coming, just like the song says, slowly and steadily, under the lamps, the ghostly Unisphere, and the hazy night sky.

By the third day runners are able to greet each other in the pre-dawn darkness and smile. The rhythm sets in. The body and mind are getting used to the idea. Al Howie is unabashedly quizzing everyone in his Scottish brogue on their sleep patterns (as he dashes by) and is astonished at Suprabha’s apparent lack of strategy and willingness to forego sleep. Al is a stranger to the New York ultra scene, and his pace has hitherto been regarded with skepticism. It is becoming clear, however, that he is determined to win.

His apparent destiny seems reinforced by the hand of fate. He turned down a sponsor over the issue of food, and while waiting in the airport read in the newspaper that his would-be flight had crashed, killing all passengers. The incident has heightened his determination; he seems to be on a special mission and in fact does look a bit like a 19th century visionary: shaggy, eyebrows over sharp eyes trained at the sky, and jutting elbows, keeping pace with his short, quick strides: most of all, though, he is here to learn about this sport. Within a few days he will declare himself eager to take up the challenge of the 1300 miler in September.

For others, foot problems are the order of the day. Yet the tone of the race is unusually cheerful. The field is not fiercely competitive and harbors few surprises. Some are making gradual comebacks after enforced layoffs due to illness or injury – Bev Cannata, Sarama Minoli, myself; others are gaining experience and steadily moving up the ultra ranks, accepting setbacks with poise and greeting well-known barriers with determination – Barbara McLeod and Al Howie, among others.

Of the up and coming set, Ronnie Wong keeps pulling all-nighters, and has the highest mileage for the day at 80, putting him firmly in third. Bruce Holtman of Baltimore holds on to a serious pace for a first multiday, sticking close to Tim Kourounis, whose inconsistent but vigorous pace is somewhat bewildering.

Sarama and Bev are sticking to a steady walking – Bev says one should not underestimate an ex-hiker.

Finally, the predicted fierce storm breaks. First there was a steady rain in the wee hours of the morning, then near-hurricane conditions throughout the day. High winds lash the park continuously for 38 hours and each runner, in turn, feels the need to rise to the occasion. Between the calculated risk of hypothermia and the sheer challenge of taking the corners straight into gale-force winds and icy rain, the mood is elevated and electric. Runners break out the Ellesse rain jackets, relics of the New York Marathon, and venture out like so many tents flapping along the course. At one point the counting structure is actually lifted and transported several feet. The counters themselves, despite the roof overhead, are unable to avoid the driving rain, and temporarily without heat they are wrapped, shivering, in plastic, valiantly yelling encouragement to the runners. The medical barracks become a huge drying rack with the urgent need for warm, dry clothes.

Finally, the predicted fierce storm breaks. First there was a steady rain in the wee hours of the morning, then near-hurricane conditions throughout the day. High winds lash the park continuously for 38 hours and each runner, in turn, feels the need to rise to the occasion. Between the calculated risk of hypothermia and the sheer challenge of taking the corners straight into gale-force winds and icy rain, the mood is elevated and electric. Runners break out the Ellesse rain jackets, relics of the New York Marathon, and venture out like so many tents flapping along the course. At one point the counting structure is actually lifted and transported several feet. The counters themselves, despite the roof overhead, are unable to avoid the driving rain, and temporarily without heat they are wrapped, shivering, in plastic, valiantly yelling encouragement to the runners. The medical barracks become a huge drying rack with the urgent need for warm, dry clothes.

At times like these the sport enters a realm reminiscent of pioneer days; when and whence relief would come was not known to mere mortals, who are trying to fulfill their daily mileage quota. Antana’s tent is ripped apart, which she feels will encourage her to give up sleep altogether. Bev Cannata, one of the first women multiday runners, is seen running at a good pace for the first time in the race. Barbara McLeod manages to spend most of the night steadily building up mileage, with Antana and Nirjhari Delong, who has recently completed the Marathon des Sables, almost keeping up. Antana occasionally enters the medical tent, explaining that she has simply had it, only to go right out again. Sarama, who at 61 has decided to make a comeback in the sport, spends the entire night on her feet because she 'didn’t have anything else to do.' Bruce Holtman runs through the night and Mike Moilamen cheerfully plugs away with the second highest mileage for the day, becoming a threat to Malcolm Campbell. The second and last casualty, Barry Feldman is advised to stop with severe blisters.